Empowerment Journey Step 5

We now know that the crossroads of whether or not we can live on less than we make will determine the type of financial life we have. If we learn to save, we can build a firewall to protect us from unforeseen expenses. However, if we spend everything we make and still have wants or needs, we’ll probably go into debt, and use someone else’s money to pay our bills.

In today’s society debt is dressed up (“buy now, pay later”), discretely hidden, and normalized so much that we may not even perceive it as being dangerous. When first presented with the opportunity to finance a purchase, your reaction may be something like mine when I first started (mis)using credit in my early 20s: “look how much more I can afford if I charge this, compared with if I had to have the cash up front!” Make no mistake, the person on the other side of the transaction is offering you credit because they stand to PROFIT by doing so. Their profit is your loss, and offering debt (AKA “financing”) is an extremely profitable business.

Debt is Bad

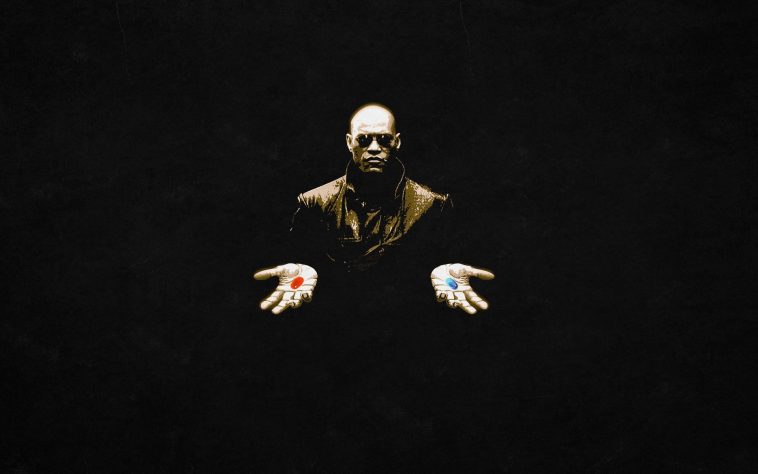

This is a sort of blue pill/red pill moment here. Many people say things like “as long as the interest rate is good and you can afford the payments, debt is no problem” Or, “as long as you pay off your credit cards every month, you’ll be fine”. Or (I’ve done this one) “I just have this card for the airline miles”. All that is great, and honestly there are situations in life where it may make sense – or be difficult to avoid – taking on some debt. Buying a home is an obvious case; most people don’t have hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash laying around. We all need housing, and renting isn’t always a great deal. You can build up equity if you own a place, and in that way your home can help you build wealth.

But many things in our lives are not necessities, and in a world where it’s easy to finance practically anything, you may find it difficult to be judicious once you start using other peoples’ money. I’ve gotten in-and-out of debt a few times in my life, and if I was able to give my younger self some advice, I’d tell him, “debt is dangerous, stay away from it”. I say this for a few reasons:

- Debt encourages us to purchase more expensive things than what we would buy if we paid cash. Since our bank account doesn’t go down when we charge things, we’re less “price sensitive”. This can make it harder to live within our means.

- Debt hinders our ability to save, because we’re too busy paying interest — which represents someone else’s investment earnings. There may not be enough left over to build our savings, which in turn can lead to more debt usage in lieu of an emergency fund.

- Debt prevents us from investing and building wealth (because we aren’t building up savings, or are doing so only slowly). It robs us of our financial freedom over time.

- Using debt puts us in a situation of obligation to other people. We feel less free, which can cause negative emotions (frustration, resentment, helplessness) that can rob us of our energy, and harm our relationships with others as well as our self confidence.

Debt or Financial Freedom: It’s Difficult to Have Both

Debt is like speed bumps on the road to financial freedom. No matter how much of a financial ninja you are about paying off your cards every month, “life happens”. An unforeseen expense, medical bill, car problem, special person you want to impress with a gift, I don’t know what it will be but it’s too easy to let a payment slip and not fully pay your balance for a month. There’s no negative reinforcement to stop you – it feels the same. You’re still paying them every month, right? So what’s the difference of having a $200 card payment that you fully pay each month, versus a $300 payment which you can only half afford if it means taking home that new TV today? Eventually the payments increase, a little at first, and then more. You get used to using credit, and form habits around it. It’s normalized everywhere, and because we’re social creatures, habits get reinforced through watching our friends, family, people we admire use it to get the things they want (“look at Rick’s new Mercedez”). Between the social aspect, lifestyle desires we all have, and strong profit motive for companies offering financing, every incentive is there for us to use as much credit as we’re able to get.

With these strong incentives to accumulate credit, if our earnings don’t keep up, or our discipline fades and we miss a payment, the interest goes through the roof.

Now they’ve got you.

Now the extra cash you SHOULD be saving to build up your financial castle … is going to MasterCard instead. Your castle doesn’t get built. And then life happens again and because you don’t have your castle built (no savings), you just go further into debt. You see people headed to financial freedom and you’re stuck at a red light.

How to Buy a Car

When thinking about big-ticket items that will be financed, there are five criteria that must be considered simultaneously to know if it’s a good deal or not:

- Total price

- Down payment

- Interest rate (the higher this is, the slower the debt gets paid off.)

- Monthly payment (can you pay this and still make your other bills?)

- Term of loan (how many months/years are you in this until the thing is truly “yours”?)

These things have to be considered all at once to know if you’re getting a good deal. But we tend to focus on one, maybe two of them at most and forget the others. Salespeople know this and exploit it all day long. Our brains have trouble properly evaluating long-term financial obligations when we’re under sales pressure combined with temptation both acting on us at once.

Take buying a car as an example. Most people do some research before walking into a dealership, so they know roughly how much car they can afford. So you’re talking with a salesperson and everything looks pretty solid. They run your credit, the financing gets approved. Monthly payment is within your price range. Great. Then the salesperson shows you a paper listing one hundred common car repair items and helpfully lets you know, “we have a warranty that will protect you from all of this. Do you want to be protected? It’s only $34 more per month”

I’ll tell you – I bit on that one! Hook, line and sinker, they got me. Because I forgot to keep all five criteria in mind, and started just looking at the monthly payment and if $34 was a good deal to be protected from all hundred of those repairs. And maybe it is. But the real cost of that warranty is more like $4000, which gets added onto the total amount of the car loan. Surprise! The car isn’t such a good deal now.

That $34 is applied to all monthly payments for the entire term of the loan, 60 payments in the case of a five-year car loan. It’s hard to keep all this in mind if your brain doesn’t naturally think in these terms (or if you don’t sell cars for a living). Most importantly, at the heart of the transaction – your using someone else’s money. What’s an extra $1000 here or there? Don’t you want the leather seats?

If you are going to buy a car at a dealership, bring pen and paper and write down each of the five items above – total price, down payment, interest rate, monthly payment, and term – and if the salesperson tries to change one item, then be sure to ask them how it affects the other four before you agree to the deal. If you feel confused, tired, or frustrated, just walk away.

Debt is the Opposite of Investing

One reason we struggle with using debt is the same reason we struggle with investing – our brains are built to think in linear, not exponential, terms.

In his 2008 book More Than You Know, veteran investor Michael Mauboussin proposes a quiz to see how well we can conceptualize compound interest. How much does one dollar today turn into after 20 years if it grows at 2%, 7%, 15%, or 20%? Write down your guesses and then look at the answers below:

| Growth rate | Ending Value after 20 Years |

| 2% | $1.49 |

| 7% | $3.87 |

| 15% | $16.37 |

| 20% | $38.34 |

Mauboussin explains the exercise:

“If you are like most people, you had difficulty properly gauging the relationship between the growth rate and the ending value. For example, it is not intuitive to most investors that an increase from 15 to 20 percent growth implies more than a doubling in value after twenty years. That’s why Albert Einstein called compounding the ‘eighth wonder of the world.’ The trick for investors is to make the compounding work for them, not against them. [emphasis added]”

If you can earn a modest investment return over a long enough period of time, your investment earnings will be compounding on themselves eventually. Your money makes money on itself. The effects of this can be dramatic. A good example is Warren Buffet; he’s been investing most of his life, yet he accumulated the majority of his wealth in his older years. The reason? Compounding. This article explains, “Effectively all of Buffett’s financial success can be tied to the financial base he built in his pubescent years and the longevity he maintained in his geriatric years [emphasis added].”

TL;DR – Buffet started early, and socked away money religiously for a long time, giving compound interest time to do its thing. And he was able to do that because his savings and investment dollars weren’t going to an exorbitant car payment. Buffet’s 2008 biography The Snowball says, “‘Spend less than you make’ could, in fact, have been the Buffett family motto, if accompanied by its corollary, ‘Don’t go into debt.‘ [emphasis added]”

When we invest, we get the power of compounding on our side. When we use debt, the eighth wonder of the world is unleashed against us, making it all but impossible to find financial freedom. It’s like punching yourself in the face while trying to cure a headache.

Your Debt, Not The Government’s

It’s common to complain about government debt but less attention is paid to the amount of debt households (A.K.A. people like you and me) accrue. Government debt is referred to as “public” debt, as it’s a shared burden on all of us. But “private” debt, i.e. the debts incurred by households and businesses, deserve our attention as well. An article published in 2020 by the St. Louis Federal Reserve notes:

“When discussing [government] debt, the media often ask whether it is too large and … how it might negatively affect the economy. Less media attention is given to private debt—even though it is at a higher level and can be just as damaging to the economy“ [emphasis added].

A 2016 post in Democracy Journal says, “Even though government debt grabs all the headlines, private debt is larger than government debt and has more impact on economic outcomes. … since 1950, U.S. private debt has almost tripled from 55 percent of GDP to 150 percent of GDP, and most other major economies have shown a similar trend. [emphasis added]”

The chart below uses data from the St. Louis Fed going back to 1951 displaying US household, business, and government debt, as a portion of US Gross Domestic Product, a shorthand for the value of all goods and services the country produces. You can see that household debt (blue line) rose from around 23% of GDP in the early 1950s to nearly 100% in 2008. Household debt declined after the 2008 Financial Crisis but remains above 70% of GDP as of this writing in Summer 2023 (around three times its 1951 level). Business debt (green line) has roughly doubled over the same period.

In the 1950s government debt (red line) was much higher than household or business debt, owing to the “New Deal” programs which sought to shepherd the country out of the Depression, and spending on the war. However household debt surpassed government debt as a percentage of GDP in the mid-1960s and remained higher until 2014. Government spending increased dramatically in 2008 as the banking system received bailouts intended to stabilize the economy, and again in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Government debt tends to spike when there is a crisis, and sort of meander along otherwise.

Governments have an advantage when it comes to paying off debt that you and I do not have, however: they can raise taxes or enact policies which have sweeping effects. So yes, at over 100% of GDP currently, government debt is high. But they have powerful tools at their disposal to address their debts. Households and businesses have limited options: pay the debt back or seek protection under bankruptcy laws.

More Debt, More Crises

High debt levels in the economy are dangerous because they slow down economic growth, and can cause financial crises. High debt leads to instability. For our economy, rising levels of private debt can result in more frequent and severe crises like the 2008 Crisis and the Great Depression. A 2012 paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) notes that after the Depression, people lost their appetite for debt and there was a 30-year period without any notable crisis. This was different from the prior century of capitalism, which had seen a crisis roughly every decade:

“[U]ntil 2008, we had all but forgotten about financial crises … as for two or three generations, going back to the Great Depression, very few such crises had occurred, and absolutely none at all occurred from World War 2 until the 1970s. … the [post-WWII] financial system was for a long time carrying low leverage ….”

“Leverage” is a fancy word for debt. We can see that the blue and green lines on the graph were much lower in the 1950s, and NBER credits these low debt levels with the smooth economic growth we saw during the 50s and 60s.

Recessions (a fancy word for a slowing economy) are bad; businesses lay off workers and people have less money to spend. We buy less stuff, take fewer trips, etc. Financial crises often lead to recessions that are larger than normal, which negatively affects everyone, so it benefits us all if there’s a way we can experience fewer of them. And one way to do that is for all of us to use less debt.

Debt is a Drag on Growth

The Democracy Journal article mentioned above notes, “… a growing body of research suggests that when private debt enters the range of 100 to 150 percent of GDP, it impedes economic growth. When private debt is high, consumers and businesses have to divert an increased portion of their income to paying interest and principal on that debt—and they spend and invest less as a result. [emphasis added]”

This isn’t just a US phenomenon; the graph below from the International Monetary Fund shows that household debt in numerous countries has risen since the 1950s, with Canada, the UK and the US currently having the highest debt.

When households and businesses have too much debt, it slows down economic growth. This is bad; higher economic growth means businesses can hire more people, and pay them more money which the people can either spend or save and invest. Paying interest on debt means businesses can’t hire workers; it means workers can’t save or invest that money. Lower economic growth endangers the financial health of all of us, and one way to avoid it is … wait for it … use less debt.

The Intervention

Debt is bad. It’s bad for us individually, and it’s bad for the economy as a whole.

The interest we pay on credit cards and loans is someone else’s profit. Why should we create juicy returns for finance companies while bankrupting our future selves, our families, and our communities? Why should we send big chunks of our hard-earned cash to credit cards every month while our savings and investment accounts collect dust?

Is it sustainable for our collective debt to equal (or surpass) the production of our entire economy? Is it worth getting walloped by financial crises so that Bank of America and Mastercard can earn ever larger profits?

Get off the treadmill. Shred the cards. Stop making other people rich.

Learn to live on less than what you make. Use the “little extra” to build your savings over time, and be your own bank. Once your savings are built up enough, you can use your own money for unforeseen expenses or large purchases. And good news – using your money has a fantastic interest rate of ZERO that never expires.

Thanks for reading! Follow me on Twitter to continue the conversation.